Zone 2 Training: What’s all the fuss about?

Those of us on social media can’t get away from the hype and discussion around so-called “Zone 2” training. Like with many discussions on social media, you might easily be mistaken in thinking that so-called “Zone 2” training is a brand-new and somehow magical training construct and the only way to achieving your endurance training goals. Whilst that is not the case, training in “Zone 2” is one of the core pillars of my training philosophy when working with endurance athletes and long-distance triathletes in particular.

In this blog, I have tried to clear up some of the confusion around “Zone 2” training and offer my rationale for why accumulating a large volume of low-intensity training is important.

What do we mean by “Zone 2”?

Before discussing why so-called “Zone 2” training might be important, we need to nail down what we mean by Zone 2. In zone 2 training, athletes and coaches use a five-zone model of exercise intensity. Zone 1 is very easy, recovery intensities, and the transition defines the top of Zone 2 from physiologically moderate to heavy intensity exercise. This boundary, which is used to define the threshold between Zones 2 and 3, is referred to by various names and estimated using different methods, e.g., the first ventilatory threshold (VT1), the lactate threshold (LT or LT1), the gas exchange threshold (GET), or even the aerobic threshold (AeT). In science, we consistently muddy the waters with our inconsistent terminologies!

So, from a physiological perspective, Zone 2 exercise refers to moderate intensities characterised by low and stable blood lactate concentrations, well-controlled ventilation, and low(ish) perceived effort (3, 4). When exercising in Zone 2, you should be able to hold a conversation relatively easily, so we might also refer to Zone 2 exercise as “conversational pace”. For more information about establishing the aerobic threshold (the top of Zone 2), read our previous blog here.

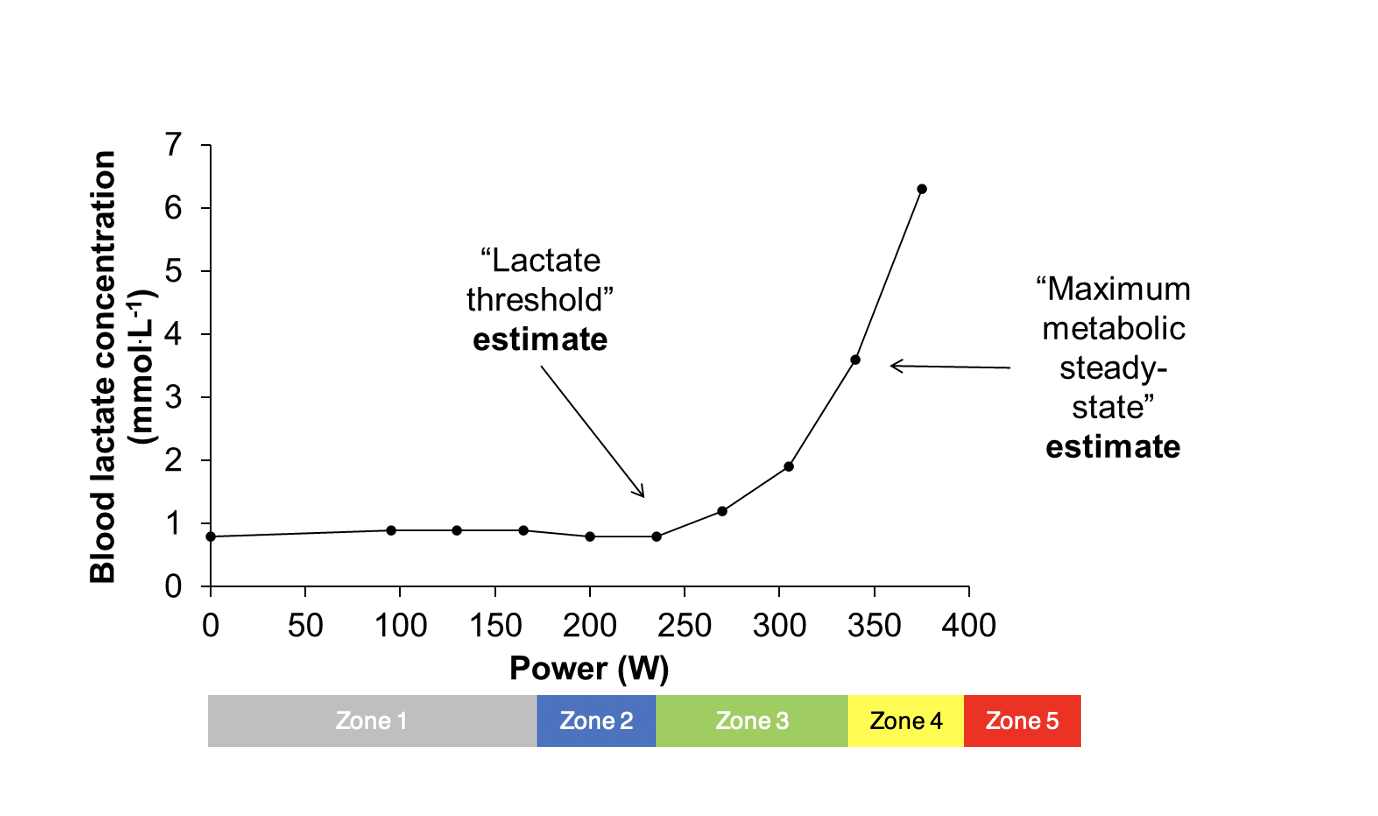

We routinely estimate the power outputs, running speeds, and heart rates achieved by individual athletes at this moderate-to-heavy intensity transition using the VT1 and LT methods. One of the fundamental reasons we do this is to define the upper intensity of Zone 2, so we can programme training and monitor the training load accordingly. Below is an example curve of blood lactate concentration plotted against power output obtained from a standard incremental exercise test with a cyclist. We identified the power output at the lactate threshold – the first rise in blood lactate concentration versus baseline values – and then used this to define the power outputs we consider to be in Zone 2.

Why train in “Zone 2”?

A question I am often asked and have asked myself is, “What is so special about Zone 2?” Why is there such hype around Zone 2 training? This is a good question, and I will do my best to offer my perspective here.

As an applied exercise physiologist, I do come straight back to physiology. We know that when working in the moderate-intensity domain under the lactate threshold, and therefore in Zone 2, the physiological stress generated is characteristically different from the physiological stress generated above it. For example, we know that the autonomic stress generated is lower, reducing the recovery required following the session compared to exercise in the heavy or severe-intensity domains above the lactate threshold. This was borne out in a controlled laboratory study of athletes by Prof. Stephen Seiler (6). Marco Altini and I recently demonstrated the same effect in a big data study of HRV4Training users (1). Therefore, regulating and controlling a significant portion of our training hours below the lactate threshold in Zone 2 facilitates the accumulation of a larger overall training volume, as these sessions do not require significant recovery periods. This is the key rationale behind polarised or pyramidal training intensity distributions (5), discussed by Prof. Stephen Seiler here.

If the rationale for Zone 2 training is only about managing stress, why not just rest between your high-intensity workouts instead? We know intuitively that accumulating a large overall training volume is likely to be a good thing, and we have physiological data to support this. A recent meta-analysis found that adaptations to mitochondrial protein content – the sites of aerobic metabolism inside cells – is linked to training volume (2). More mitochondria will likely allow us to achieve higher power outputs and running speeds at the physiological thresholds and, therefore, faster sustainable paces for our endurance events. More mitochondria also allow us to metabolise fat at faster rates during exercise. So, accumulating a large overall training volume, which we can achieve via careful intensity discipline whereby a significant amount of training is performed in Zone 2, likely helps us generate some of the key adaptations we seek in our training programmes.

An outstanding study published last year allows us to put even more meat on the bone. A study led by McMaster University in Canada found that 12-week blocks of low-intensity and sprint interval training enhanced mitochondrial protein content in fast-twitch type II fibres, increased mitochondrial protein content in slow-twitch type I fibres was only observed after the low-intensity training block (7). These data, therefore, suggest that lower-intensity training is somehow inherently favourable for inducing mitochondrial adaptations in slow-twitch fibres and so needs to be included in the training programme of endurance athletes, where the performance of slow-twitch muscle is critical for performance.

It's not all Zone 2

Hopefully, I have demonstrated above why I think accumulating a significant portion of your training week – perhaps 70-85% - in the so-called “Zone 2” might be beneficial for endurance athletes. It is important to recognise here that in the build-up to an event, we will need some training at higher intensities above the lactate threshold in Zones 3-5. High-intensity training is great for disturbing homeostasis, inducing significant stress, and driving adaptations – some of which are important and distinct from the adaptations that occur with Zone 2 training. For example, the meta-analysis I mentioned above showed that training intensity is linked to adaptations to mitochondrial respiratory function (2). So, whilst training volume seems important for building mitochondrial protein, the intensity may be important for tuning them up to work most effectively.

The types of higher-intensity sessions we perform will vary depending on the goal of the session and the training block. We discuss how to programme high-intensity training at length on our courses and provide sessions and programmes in line with my training philosophy in the Endure IQ Squad.

Summary

Hopefully, you can see why Zone 2 training – close to but below the lactate threshold – is a core component of the training programmes I put together for endurance athletes, but not the only intensity we use!

- Zone 2 training induces relatively little physiological stress and therefore helps facilitate the accumulation of a large overall training volume.

- Training volume appears to be linked to positive adaptations to mitochondrial protein content, which is some of the key objectives of endurance training.

- Lower-intensity training appears favourable for building mitochondrial protein content in the slow-twitch, type I fibres we rely on in endurance sports.

- Higher-intensity training generates other key adaptations and should be carefully included within our training programmes.

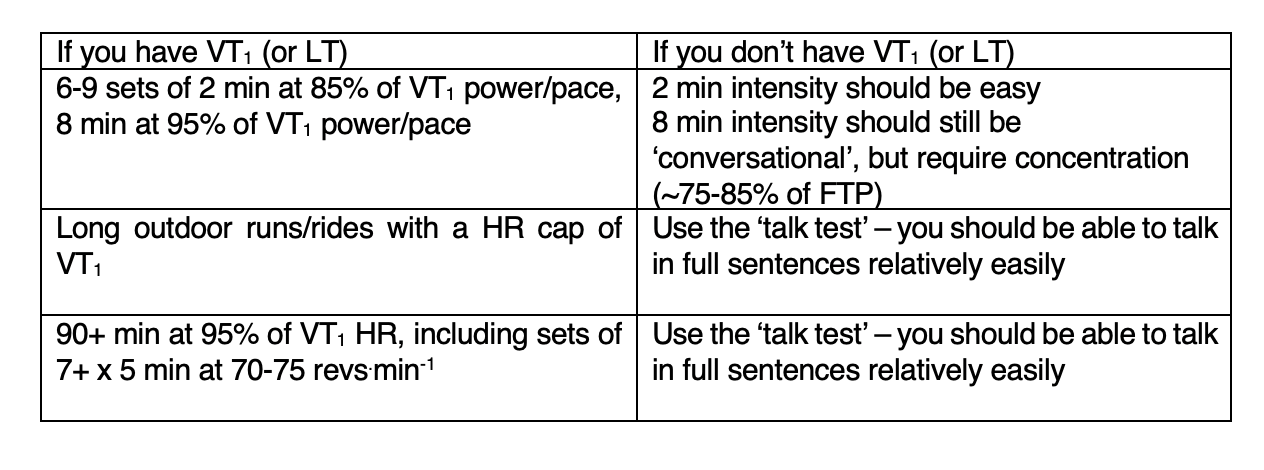

Below I have included a series of Zone 2 training sessions you might use in your training.

EndureOn!

References

- Altini M, Plews D. What is behind changes in resting heart rate and heart rate variability? A large-scale analysis of longitudinal measurements acquired in free-living. Sensors 21: 7932, 2021.

- Granata C, Jamnick NA, Bishop DJ. Training-induced changes in mitochondrial content and respiratory function in human skeletal muscle. Sports Med 48: 1809–1828, 2018.

- Jamnick NA, Pettitt RW, Granata C, Pyne DB, Bishop DJ. An examination and critique of current methods to determine exercise intensity. Sports Med 50: 1729–1756, 2020. doi: 10.1007/s40279-020-01322-8.

- Maunder E, Seiler S, Mildenhall MJ, Kilding AE, Plews DJ. The importance of ‘durability’ in the physiological profiling of endurance athletes. Sports Med 51: 1619–1628, 2021. doi: 10.1007/s40279-021-01459-0.

- Seiler KS. What is best practice for training intensity and duration distribution in endurance athletes? Int J Sports Physiol Perform 5: 276–291, 2010.

- Seiler S, Haugen O, Kuffel E. Autonomic recovery after exercise in trained athletes: Intensity and duration effects. Med Sci Sports Exerc 39: 1366–1373, 2007. doi: 10.1249/mss.0b013e318060f17d.

- Skelly L. E, Gillen JB, Frankish BP, MacInnis MJ, Godkin FE, Tarnopolsky MA, Murphy RM, Gibala MJ. Human skeletal muscle fiber type-specific responses to sprint interval and moderate intensity continuous exercise: acute and training-induced changes. J Appl Physiol 130: 1001–1014, 2021.

JOIN THE SQUAD

Take charge of your performance with proven training programs and workouts, adjustable to your needs, in the Endure IQ Training Squad.

LIMITED OFFER